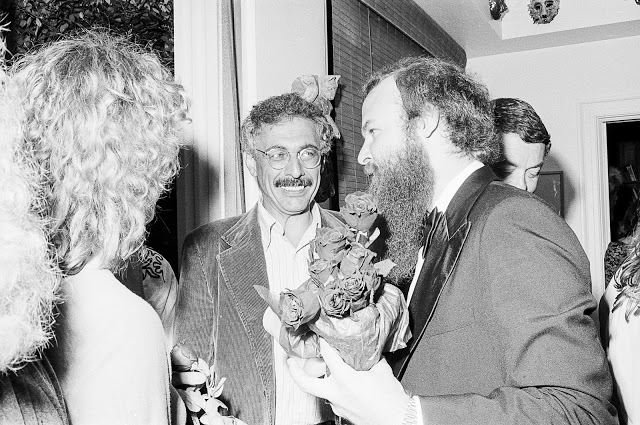

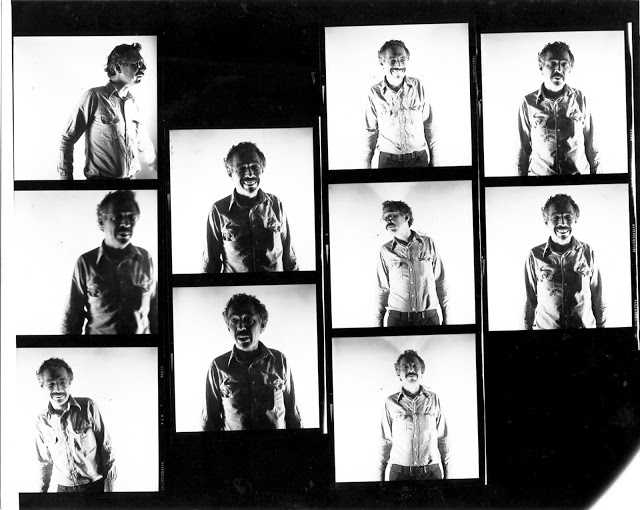

In 1976, Paul was commissioned by Jim Harithas, then the CAMH Executive Director, to document artists and exhibitions for the museum’s catalogues. This landed Paul in the center of a burgeoning artistic community— in effect, Paul was able to photograph many of the artists, patrons, and art-world leaders who have shaped Houston’s art community since the 1970s and who have represented Houston in the national and international art arenas since then. Later that year Harithas offered Paul the first solo photographic exhibition by a woman at the museum. Entitled Suzanne Paul: Photographs, Paul credits this exhibition with launching her professional career.

James Harithas, himself a pioneer in the arts, came to Houston in 1973 to pursue his great passions — cementing the legacy of abstract expressionism, supporting powerful political art, and championing emerging artists. These efforts merged in his assumption of the position of Director at the Contemporary Arts Museum (CAMH), which followed positions as Director at the Corcoran Gallery in Washington and Director of the Everson Museum Of Art in Syracuse.

In an 1979 interview with Sandra Curtis, Harithas said “I thought Houston was wide open… an opportunity to start fresh.”

Not only did he offer discerning support to local and regional artists, but, from his past experiences he brought with him a new philosophy on the contemporary role of the art museum model and how such an institution might fit within a community to impact the tenor of its art-making and the representation of its artists.

Harithas recalls, “In that period I broadened the notion of what a museum could do. I knew a museum was a political force … it became increasingly clear to me that a museum could do somewhat more than show art — it could also develop programs that had an underlying aesthetic … I felt that a museum had to be free- form.”

He continues, ”It was also during that period that I began to develop the idea of finding curatorial help from other disciplines. Like the photography curator actually came straight out of television, and was a newsman. In a culture that was reaching this … a mass culture, it was really important to have on the staff people who had really direct experience … There was a point where it was clear to me that my ideas had now expanded sufficiently. I wanted to go further into media, and I also wanted to go further into the phenomena of local culture, which I was becoming increasingly aware of … I was looking for originality — which I found in Houston … and which existed as part of a regional phenomenon …”

The museum director emphasized, “My reason for coming [here] was that I really liked Houston … But the main activity of the institution [was] identifying the artists in Texas … the idea of showing local boys … and particularly the idea of showing people who needed their first show in order to go on to make their better shows” (Harithas).

As New York based critic and poet Raphael Rubenstein notes in a Brooklyn Rail interview, “After walking away from a career as a prominent curator and museum director, Harithas spent some years in the wilderness (following paths that often led through war-torn Central America) before reemerging to found two pioneering institutions, both in Houston: the Art Car Museum and the Station Museum. The first embodies Harithas’ dream of creating a working-class museum that celebrates a vernacular art form; the second is one of the most vital (and truly alternative) spaces in the country. It has hosted stellar solo exhibitions of major American artists such as Mel Chin, Salvatore Scarpitta, and Norman Bluhm, and presented powerful group shows of new art by Palestinian, Colombian and Mexican artists that illuminate the tragic, violent circumstances of those nations. Thanks to Harithas, the Station Museum consistently mounts exhibitions that no other American art institution has the guts or vision to tackle.”

***

Content originally published by Theresa Escobedo, here, on 3.17.17