Happy New Year and welcome to the beginnings of our 2020 blog series! We have had such vast growth and momentum at the gallery recently that we had to let this go for a while, but we are so happy to start again!

Today I am going to focus on our artists who currently have exhibitions at Deborah Colton Gallery: Ushio Shinohara and Noriko Shinohara, alias “Cutie and the Boxer.”

Born in Tokyo in 1932, Ushio Shinohara (nicknamed “Gyu-chan”) is a Japanese Neo-Dadaist artist and international Pop painter who has lived and worked in the United States since 1969. His parents, a tanka poet and Japanese painter, instilled in him a love for artists such as Cézanne, Van Gogh, and Gauguin. Most recently known for his exuberant boxing paintings, which are artifacts of his performances, Ushio Shinohara works in several mediums, including painting, printmaking, drawing and sculpture.

Ushio’s bright and frequently oversized work has exhibited at prestigious institutions internationally, including the Hara Museum of Contemporary Art; Centre Georges Pompidou; the Guggenheim Museum, New York; the Japan Society, New York; the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo; the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Pusan; the Dallas Museum of Art, and the Tate Modern, among others. His work was also featured in International Pop, a landmark exhibition at the Walker Art Center that chronicles the global emergence of Pop art from the 1950s through the early 1970. A New York Times article on the exhibition reads: “Ushio Shinohara… engaged in a practice that might have been called punk if the concept had existed then…” reinforcing his position as a leading figure of the avant-garde art world.

Now to take a more personal shift, when I was first introduced to Ushio’s boxing paintings I was still in school at the University of North Texas. As a budding art student honing my critical eye, I must admit that the pressure to have something to say in class critiques — the desire to establish a voice, and demonstrate one’s competence — often led to a hasty judgment of the given subject matter. Ushio’s patented boxing paintings were no exception, and as such, I designated them as a gimmick. Much like how one may have determined Pollack’s style to be a gimmick; the idea is surely novel, but the novelty is quickly diminished across reiterations. I’ll explain why I was wrong, but first I need to provide some more context.

I’m sure you’ve heard the expression “my child could paint that,” which is a common critique regarding abstract expressionism. However, the reason this critique should be dismissed is because it considers only the treatment of the materials, while altogether ignoring the exposition of the artwork. In Ushio’s case, the apparent flippancy demonstrated in his boxing paintings often overshadows the commentary, and it seems to me that this is an issue he has grappled with for over half a century.

In 1960 Ushio helped found the Neo-Dadaism Organizers. Their mission: deviate from any conventional form of art. Akin to European Dadaists, who’s art sought to reveal the customary and often repressive conventions of logical order and rationality, the Neo-Dadaism Organizers embodied a similar ethos. This can chiefly be seen in akushon, meaning “action”, which is the practice of emphasizing the human body as an artistic medium. In particular, its aim is to shock the audience via impulsive and sometimes disturbing performances. Depending on the means and magnitude of such a performance, the disturbance may seem to take precedence over the object of the art.

Thus, the premise of the artwork, and why it remains challenging to some, is because the object of the art is not the artwork itself. Instead, the artwork itself is more like a consequence — an epiphenomenon if you will. The real substance of the artwork lies in the sensibility, or ethic, with which the artist is using to communicate with you, the viewer. For Ushio, this sensibility is encapsulated in what has become his personal trinity “be speedy, beautiful, and rhythmical.”

I must confess that in the beginning the prospect of his “wild man” personality did not appeal to me, and in my haste to make a judgment, I let that prospect overshadow a more meaningful interpretation. Though now, with a better understanding of Ushio’s sensibility, I think you’ll find there is actually a great depth of complexity and sophistication in his artistic production.

For Noriko, the subject matter is a different story, literally. Whereas Ushio’s work is primarily drawing upon the sensations of the marks being made, Noriko’s work is presented as a narrative. Noriko’s work has been exhibited frequently in New York and Japan, and is part of the permanent collections of the Davis Museum and Cultural Center at Wellesley College.

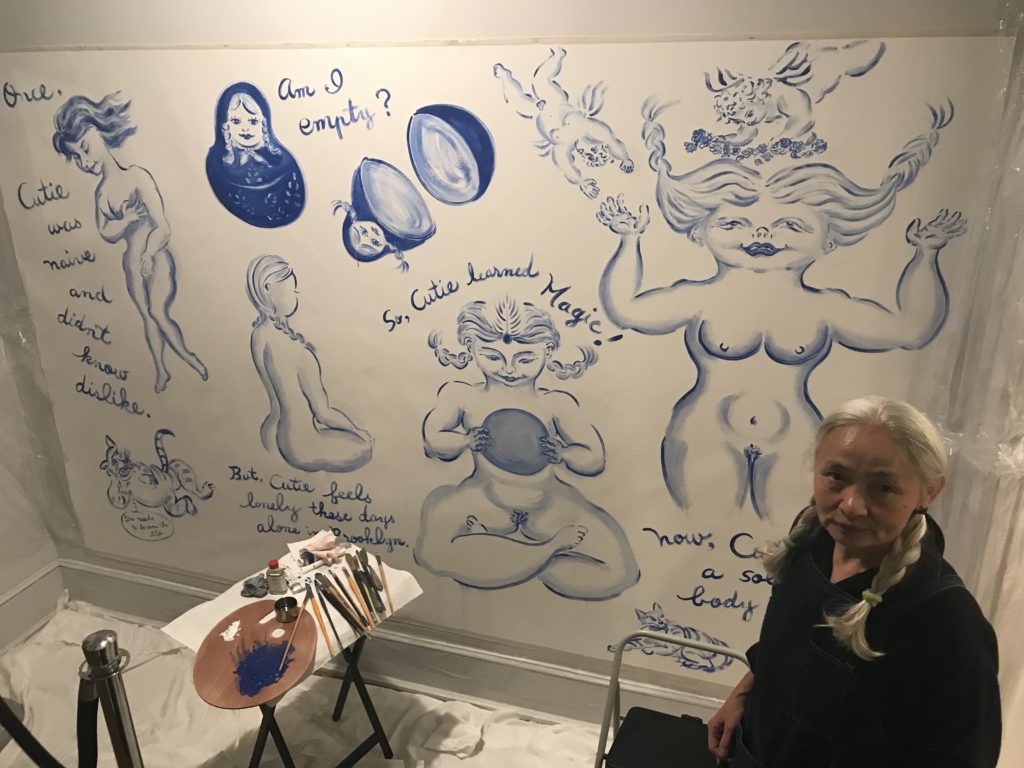

Noriko Shinohara was born in 1953 in Takaoka City, Japan, moved to New York in 1972 to study art, and soon met Ushio in 1973. She has worked as an artist for many years, but the work she is best known for is her Cutie and Bullie series. Since beginning this series in 2006, it now includes drawings, paintings, and prints featuring her characters Cutie and Bullie, and gives us a glimpse into the dynamic between herself and Ushio. Truthful to the point of discomfort, the works which chronicle Cutie and Bullie follow Cutie’s early trials of being married to an alcoholic older man and the difficulty of being an artist in New York.

The scenes are graphic representations inspired by events highlighted in the award winning documentary Cutie and the Boxer. The film was nominated for the 2014 Academy Award for Best Documentary, placed second in Audience Awards during the 2013 Tribeca Film festival, and earned Special Mention in Grierson Awards for the London Film Festival. Cutie and the Boxer won Best Director Award at the 2013 Sundance Film Festival, where the committee cited: “It’s rare to see a film so beautifully crafted in all aspects. It captures the complex nature of love and art in a mesmerizing and deeply human way.” The film was also nominated for Grand Jury Prize at the same festival.

On the surface, the imagery appears light and playful. The line-work and color palette of her illustrations have an outward pretense of levity, adolescence, and humor. However, these conditions are underscored by much deeper psychological motifs. Marked by growing pains characteristic of a coming of age drama, Noriko’s story chronicles the projection of herself — a character named Cutie — as she contends with the harshness of reality. Drawing distinctions between her experiences and her expectations, Cutie learns the difference between being idealistic and pragmatic. The imagery, maintaining the likeness of a picture book, invites notions of mysticism and fairy-tale. Yet, as the narrative unfolds, the strength of Noriko’s metaphors begin to dissolve through the allegory to reveal the real-life trials of an individual becoming disenchanted with her circumstances.

As one comes to understand the veiled comparison between herself and Cutie, the buoyancy of her figures cascades from something symbolic of simple light-hearted narration into an effigy actual consequence. In this process, the story of Cutie is an analogy for Noriko: as the tone of the Cutie’s story inflects from one of youth and amusement to one of rumination and humility, so does the viewer’s impression of Noriko. Furthermore, I only imagine that for Noriko Shinohara, the story of Cutie is a monument to her own artistic culmination into who she has become today.

Written by Grayson Chandler

All works of Ushio and Noriko Shinohara Available through Deborah Colton Gallery